I spent a lot of my childhood at my Grandmother’s house. It was as fun as any Grandmother’s place — there were trees to climb, neighbor kids to battle in street football, and sidewalks for optimal Big Wheel riding with my cousins.

And of course, there were rules. Many of them were created to protect furniture and family heirlooms from the destructive power of small, uncoordinated children who cared nothing for front room furniture and the “good plates” in the china cabinet. Those kinds of rules were eased as we got older and more respectful of the fact that not everything in the front room can be turned into a fort, or mass transit for my G.I. Joe. I mean, it COULD, but apparently the practice is frowned upon in grown-up circles.

There was always one rule that stood firm, a timeless directive that was followed by young and old alike: Quiet Time

Strategically placed after “All My Children” and before Oprah, Quiet Time was an uninterrupted two-hour block of silence. The TV went off, and children were required to either go outside and play, take a nap, or read quietly. These terms were non-negotiable; any violation would be met with her warning call of “Hush that mouth up!” from any corner of the house. If you knew what was good for you, you happily took the note.

While Grandmother moved around the house doing whatever Grandmothers did, I got lost in stories. I used Quiet Time to devour all the great works from the masters, like Beverly Cleary, Judy Blume, and Thomas Rockwell. I studied the biographies of people like Nat Turner and Guion Bluford. I read the Encyclopedia Brown serials and the actual encyclopedia. I followed the flowcharts of medical diagnostic books like they were adventure tales, cultivating my charming dash of hypochondria in a pre WebMD world. I was a sponge, soaking up whatever I could so that I could wring out facts in front of adults and impress them.

And when I wasn’t reading, during Quiet Time, I was thinking. By age 9, I realized that imagining the couch as a race car was nowhere near as fun —or productive — as drawing up plans to turn the couch into a real car. Among my many other inventions were the original designs on the hover boards that are featured in the blockbuster hit Back to The Future Part II. I am CERTAIN that Universal Pictures saw my work and applied it to the film they produced, but my lawyers tell me that the case is just too expensive to take to trial. IP lesson learned, I guess.

I was thinking about those days this weekend, as I made breakfast in the morning silence of my kitchen. As I pulled out pots and pans, a peace came over me that I had known before, but hadn’t experience in a while. But then it hit me: I was 9 years old again, on that green carpeted Wilson Ave. floor, in my own world. It was Quiet Time peace, where i wasn’t busy telling myself what I couldn’t do.

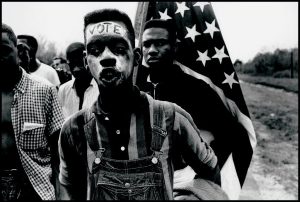

As a young, Black woman in rural 1930s Georgia, my Grandmother was surrounded by people who had to value work before themselves, just to eke out a living. She and my Grandfather joined the Second Great Migration out of the south and settled in Ohio, where they found better jobs and made a large family. I often think about how she felt about that huge life transition — if she thought that she was better off by moving away from everything she knew. During Quiet Time, I would often catch her in moments of stillness, in between her hands of Solitaire or reading from her Bible. I wonder in those times, if that’s what was on her mind.

Dementia took hold of Grandmother before we forgot how to live without a screens in our pockets. I can guarantee that between 2p — 4p EST, she would have given no fucks about your notifications.

Adulthood comes with sudden pains and lingering responsibilities that take our time and demand our presence. But as I get older I, my Grandmother’s truth becomes clearer.

Sometimes you need to sit down, and hush.